Sep. 17, 2025

Proposing a New Concept of Artificial Intelligence that Mimics Human ThoughtWhat Is Human Thought?

When people think of artificial intelligence (AI), they often imagine systems that learn from large amounts of data. However, at the Toyota Motor Corporation's Frontier Research Center, there are researchers aiming to overturn this common view by developing a different kind of AI*1-2. We interviewed Dr. Fukada about his research.

Is Current AI Truly Intelligent?

- Thank you for joining us today. You're working on AI research, correct?

- Fukada

- Yes. Intelligence powered by AI is crucial in mobility and all other fields. However, today's AI faces various problems, and I am exploring alternative approaches to address them.

- So, current AI still has many issues?

- Fukada

- Let me share an example. Take the popular large language models (LLMs): although they can generate sentences that sound natural, they don't truly understand meaning and cannot solve applied problems*3-4. Our brains can also string words together based on learned patterns, but LLMs only do this―they lack what you might call a "thought process." While they can write programs, which may seem highly logical, that's not really the case. LLMs are improving daily, but I believe there are limits to their current trajectory. For instance, a 99% correct answer rate is excellent for quiz questions, but if there's a 1% chance of error in situations involving human life or rights, it's unacceptable. Moreover, with a hundred million people, there are a hundred million unique circumstances, and many problems may be unprecedented. Solutions to such novel issues are not found in training data. In those cases, accurate logical reasoning is key to finding solutions. To realize a society where no one is left behind, I want to build AI that can reason logically and precisely.

- Precise logic sounds rigid, though.

- Fukada

- Rigid logic isn't precise. For example, laws aren't perfect―their true purpose is fairness and human happiness. Precise reasoning achieves accurate yet flexible reasoning that traces back to these fundamental purposes, and I believe it's possible. This is my goal.

- However, human emotions aren't logical―how do you address that?

- Fukada

- Logic doesn't deny emotions. Human feelings should be valued above all―they are the starting point. Then, to fulfill those feelings, we think logically about what to do.

A New Form of AI―Encountering Two Academic Fields

- So you're aiming for AI with precise logical reasoning. How do you build it?

- Fukada

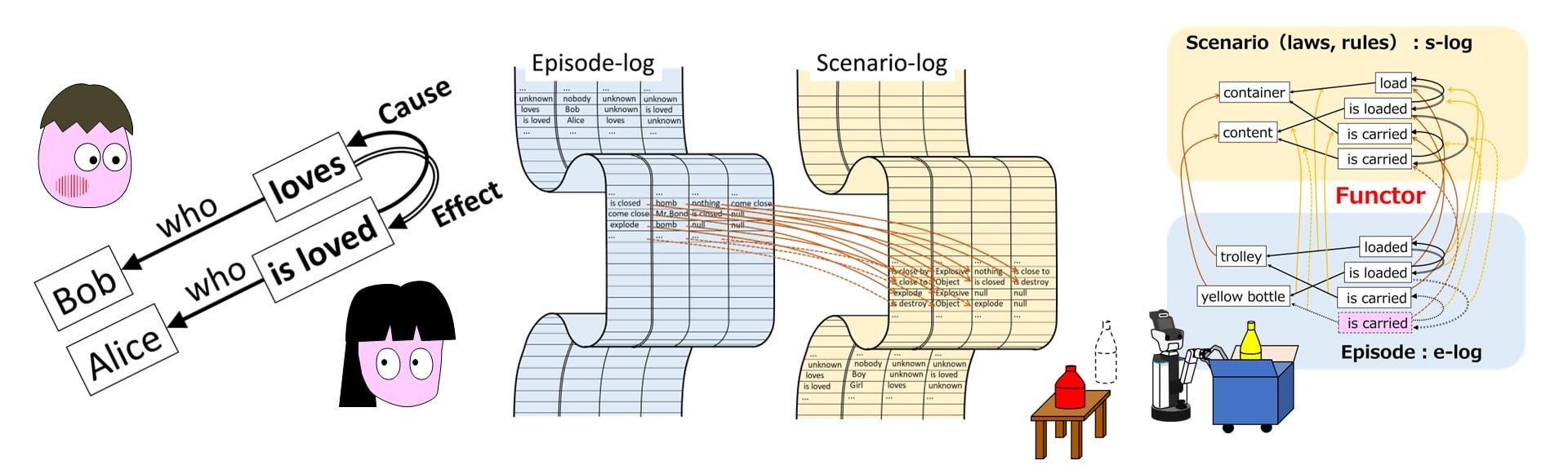

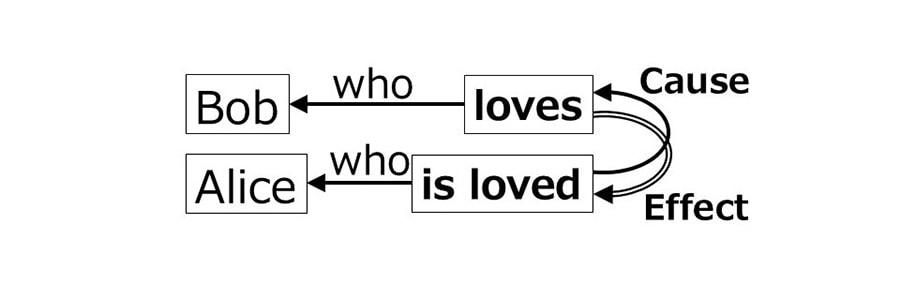

- I began by considering a way to represent an event that mimics human thinking mechanisms. Consider the example "Bob loves Alice." Humans tend to represent relationships with arrows, drawing an arrow labeled "loves" from Bob to Alice, but this doesn't fully capture the situation. I realized that Bob has his own story, and Alice has hers―this can't be expressed with just one arrow. So, I first place the action of "loves." Since Bob is the one who loves, I connect "loves" to Bob with an arrow labeled "who."

- So love comes first, right?

- Fukada

- The main subject of the story is the action of "loves." That was an important insight. Alice, on the other hand, has her own story: "being loved." There's an action of "is loved," and I link this to Alice with an arrow labeled "who." I also connect "loves" and "is loved" with a causal arrow, indicating cause and effect (Figure 1). Although it looks complicated, it's actually simple because each action is associated only with an actor. Any story consists of such chains of events, which are referred to as "episodes" in this study. This system can describe any episode, so I named it episode-log, or e-log for short.

-

- Figure 1: An e-log describing "Bob loves Alice"

- So actions, not actors, are the main subjects. Where did this idea come from?

- Fukada

- My encounters with cognitive science and a field of mathematics called category theory were decisive. Cognitive science taught me how we understand the world, and the idea that actions are the primary elements of an event came from this. Category theory deals with systems connecting points (objects) by arrows (morphisms, see Column 1).

- So it's not deep learning?

- Fukada

- That's right. Deep learning simulates neural networks and excels at tasks like image recognition, but I believe it struggles with logical reasoning. Our brains are unusually large among living things, seemingly to handle difficult logical reasoning. So, without focusing on neural networks, I developed e-log.

What Is Thought?

- How will you perform logical reasoning going forward?

- Fukada

- Logical reasoning is a process of comparison with rules or laws. Mathematics―specifically, category theory―enables this process. Using an operation called a functor (see Column 2), the process compares an e-log that describes an event with another data set that records rules or scenarios, which I call scenario-log, or s-log. If something matches a rule, we can predict what will or should happen next. For example, when you hear "Bob loves," you wonder, "Whom?" Right? This is logical reasoning―comparing to the law that "if there's loving, there must be someone being loved," and inferring that there must be a recipient.

- The law of love, huh!

- Fukada

- That was a simple example, but more complex reasoning―like solving mysteries or math problems―follows the same extension (see Column 3). The system can also perform reasoning tasks like summarization or planning by combining scenarios.

The Birth of Cognitive-logs

- Fukada

- In addition to e-log and s-log, I've developed a system called be-log to describe relationships expressed by the verb "be," such as "A swallow is a bird." I call the collection of these systems cognitive-logs.

- You'll implement these in computers, right?

- Fukada

- These cognitive-logs can be converted to a relational database (Figure 2), which is an established technology and easy to implement. Logical reasoning using category theory involves searching for correspondences between arrows and actions, and this search is well-suited to quantum computing. Japan excels in this field, so I'm optimistic.

-

- Figure 2: Three representation formats for e-log

- This is quite different from deep learning.

- Fukada

- Actually, I also have ideas for using deep learning. The relational database format is similar to a language where each sentence has four words. That means...

- So, can you process it with LLMs?

- Fukada

- Exactly. When I ask a math expert, they might say, "If you do this and that, you may solve it," seeing the answer intuitively thanks to training. Such intuitive thinking might be replicated with LLMs created by deep learning. By combining deep learning with category-theoretic operations, we might achieve quick, intuitive insight followed by precise reasoning.

Applications in Cognitive Science

- Fukada

- While I referred to cognitive science to create cognitive-logs, it could also be used in cognitive science research itself.

- So it's not just for AI applications, is it?

- Fukada

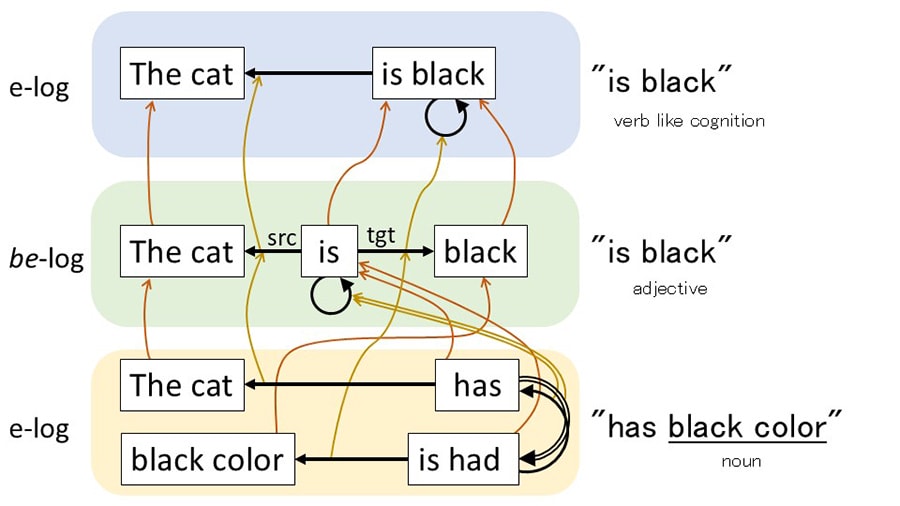

- For example, in linguistics, verb systems are almost universal across languages, but adjectives show much diversity. Japanese uniquely has adjectival verbs in addition to adjectives. A Japanese adjectival verb "makkuroda" means "strongly black" and has the nuance of "becoming black," and "having a black color" also exists. In cognitive-logs, these can be shown as equivalent by functors, which may help explain the diversity of adjective expressions (Figure 3).

-

- Figure 3: Transformation of the expression "black cat"

Different cognitive-logs corresponding to different expressions are connected by functors, showing their equivalence.

The Path to Realizing New AI

- So you're ready to mimic human thought?

- Fukada

- Not quite. Our brains are massive systems with many unknowns. One particularly challenging aspect is the mind simulator: humans are born with the ability to imagine and reconstruct others' minds*5. This function is central to our cognition―for example, even in law, people are judged based on intent or purpose, which are mental elements invisible to outsiders. That's remarkable. When recognizing events, humans classify actions by their intentions. For example, whether you carry something by hand or by truck, the movements of the arms and legs are entirely different, but the intent―changing the location of the object―is the same, so both are considered "carrying." With "love," we even perceive invisible events happening only in the mind. Inferring others' intentions may be deeply embedded in logical reasoning, and uncovering its mechanism is a major interest.

- What are the challenges in implementation?

- Fukada

- One is the amount of work required. Eventually, AI will learn on its own, but in the initial stages, "common sense" knowledge must be input manually. Instead of large amounts of training data, a qualitatively different kind of work is needed. Another challenge is that this method differs greatly from the current mainstream approaches, making acceptance difficult. I'll gradually increase the number of people who understand it.

- Finally, how do you hope this technology will be useful?

- Fukada

- That question is connected to why I was born into this world. Honestly, I don't know―it's an eternal question. People say everyone is born with a role to play. Even as the inventor, I can't fully envision how cognitive-logs will be used or if it will truly bring happiness. But I believe that someday, perhaps in ways I never imagined, it will be useful somewhere in the world.

Column 1: What Is Category Theory?

-

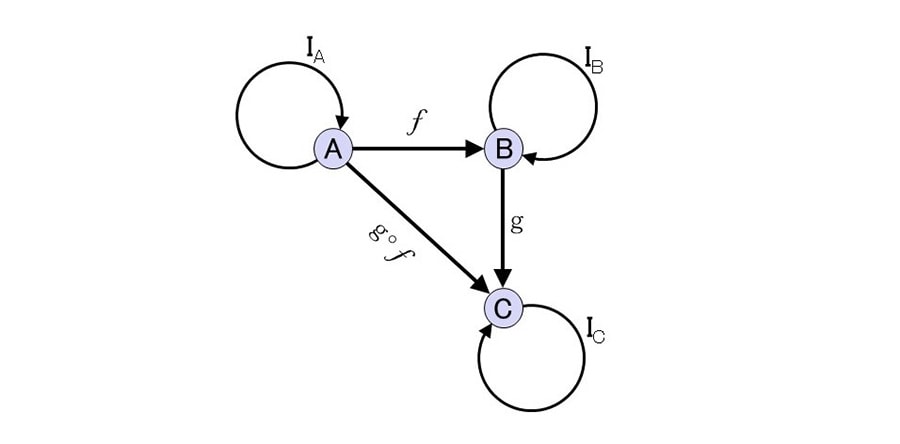

- Example of a category

A category consists of points called objects connected by arrows called morphisms, with the composition of arrows always possible. For example, the composite of arrows f and g, written g◦f, always exists. Every object has an identity morphism (IA, IB, IC), which returns to itself. Identity morphisms are often omitted unless needed.

Column 2: Functor Operations

-

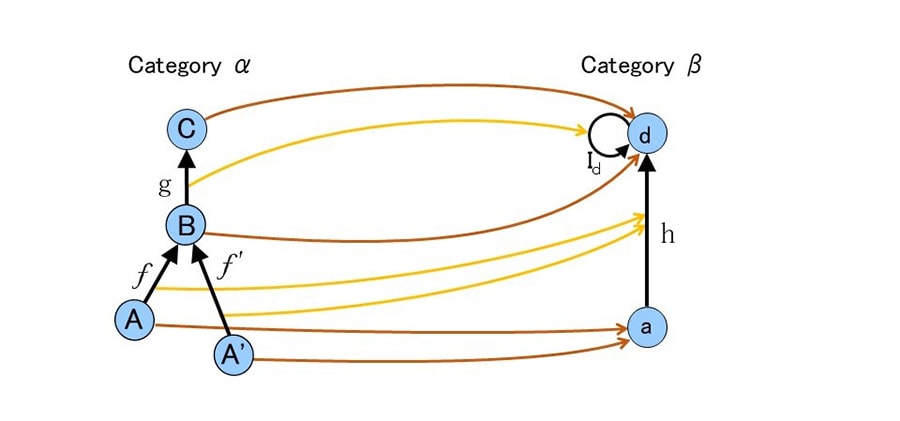

- Example of a functor

A functor connects two categories with arrows, and consists of two types of arrows: those that link objects to objects and those that link morphisms to morphisms. The rule for functors is that the connections between morphisms in the original category are preserved in the target category. The categories connected by a functor do not always need to have the same shape, and often, there can be multiple possible functors (for example, in this case, matching "B" with "a" is also possible). This flexibility of functors enables various types of logical reasoning, such as transformations at an abstract level.

Column 3: Example of Logical Reasoning Using Functors

-

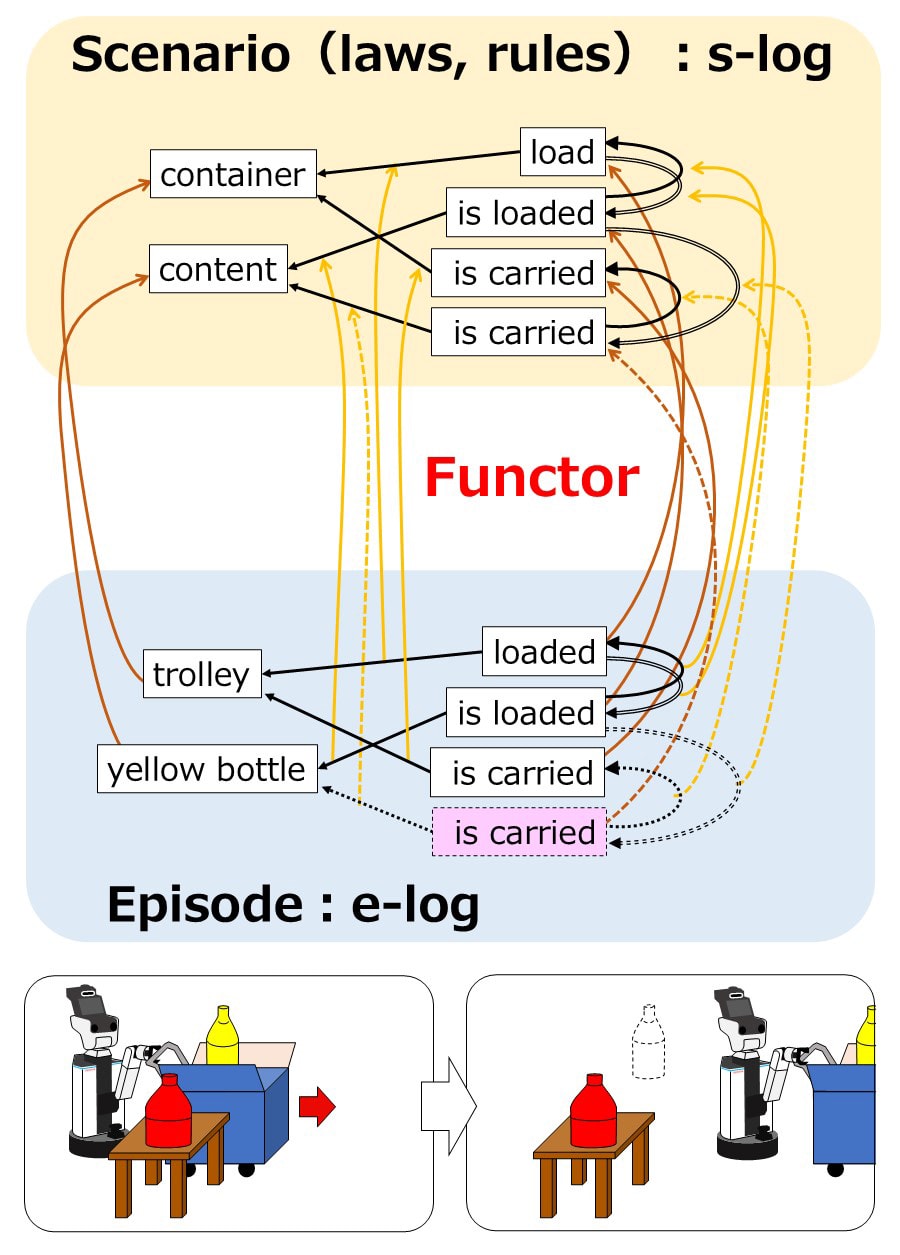

- Comparison between an e-log that describes a real episode and an s-log that records a rule

Suppose a yellow bottle is placed in a trolley, and a robot carries the trolley (bottom e-log). This matches the rule "if you carry the container, the contents are also carried" (top s-log), so you can predict that the yellow bottle will be carried along with the trolley (the "carried" shown in pink and the surrounding dashed arrows). The red bottle does not match and will not be carried. The functor is the correspondence between trolley→container, yellow bottle→contents, and the actions/arrows. It may seem like common sense, but predicting that the yellow bottle is carried is logical reasoning.

Author

Yoshiki Fukada

Collaborative Robotics Research Group, R-Frontier Div., Frontier Research Center

References

| *1 | Fukada Y., "Action is the primary key: a categorical framework for episode description and logical reasoning", arXiv:2409.04793 |

|---|---|

| *2 | Fukada Y., "Logical reasoning using graphical networks and its refinement using category theory", The 39th Annual Conference of the Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence, 2L4-GS-1-02 (2025) (in Japanese) |

| *3 | International Research Center for Neurointelligence | The University of Tokyo | Institutes for Advanced Study: AI overconfidence mirrors human brain condition A similarity between language models and aphasia points to diagnoses for both (May 15, 2025) |

| *4 | Mancoridis M., Weeks B., Vafa K., and Mullainathan S., "Potemkin Understanding in Large Language Models", arXiv:2506.21521 |

| *5 | Brüne M. and Brüne-Cohrs U, Theory of mind―evolution, ontogeny, brain mechanisms and psychopathology, Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, Volume 30, Issue 4, 2006, Pages 437-455 |

Contact Information (about this article)

- Frontier Research Center

- frc_pr@mail.toyota.co.jp