Jun. 17, 2024

Genki-KûkanTM Research Initiative (Part 5)Exploring the Restorative Effects of Nature from a Psychological Perspective

Toyota Motor Corporation's Frontier Research Center (Toyota) and Toyota Central R&D Labs., Inc. (TCRDL) are working jointly on the Genki-KûkanTM Research Initiative to develop spaces that can improve people's mental and physical well-being*1-4. In Part 4, we discussed the observable effects of nature on the physiological state of individuals (autonomic nervous system and brain activity). In Part 5, we spoke to members of this research, Masayoshi Muramatsu, Kenro Tokuhiro, and Akinori Ikeuchi, who are engaged in research on the effects from a psychological perspective to explore the simple question of "Why do we feel healed in nature?"

- What research has been done on the psychological effects of "healing through nature"?

- Muramatsu

- According to the literature, there is a record*5 from ancient Rome suggesting that nature helped alleviate the noise and congestion of urban areas. However, comprehensive research on this topic started in the 1970s. One well-known study is Roger Ulrich and others' "Stress Reduction Theory*6," which suggests that humans have an innate preference for water and green-rich natural environments and that positive emotions derived from such environments can alleviate stressful conditions.

- Tokuhiro

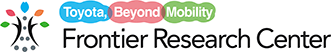

- One particular study we are focusing on is the "Attention Restoration Theory (ART)*7" by Rachel and Stephen Kaplan, which emphasizes the cognitive processes of individuals (Figure 1). According to this theory, two types of attention are important: One is called "directed attention," which refers to the sustained focus required for activities such as office work. Since prolonged directed attention can be very tiring, it can lead to frustration, loss of concentration, and an overall negative psychological state. The other is called "effortless attention," which comes into play when something beautiful or interesting catches our eye. Effortless attention is less prone to fatigue and is said to help in the recovery of directed attention. In other words, an environment with many elements that promote effortless attention can be considered a "restorative environment."

-

- Figure 1 Attention Restoration Theory

- Ikeuchi

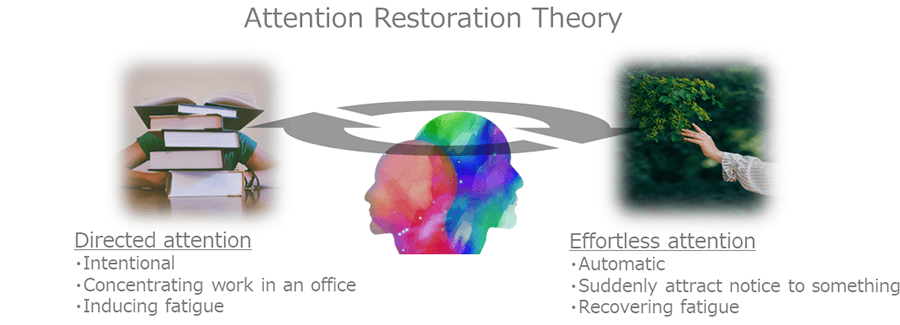

- ART identifies four elements (restorative components) that promote effortless attention (Figure 2). "Being Away" refers to the ability to detach oneself from everyday life and refresh. "Fascination" involves being captivated and drawn in by something of interest. "Extent" refers to physical or psychological expansiveness. "Compatibility" refers to the environment aligning with one's purpose and behavior. In lush natural environments, for example, the play of sunlight through the trees or the murmur of a stream can help one detach from daily life, be captivated by the beauty of nature, and feel the expansiveness it offers. I believe many of you can relate to the fact that such environments contain numerous restorative components that promote effortless attention.

-

- Figure 2 Four restorative components assumed by Attention Restoration Theory

- It is important to incorporate many elements of a "restorative environment" to create a soothing space, isn't it?

- Muramatsu

- That's right! So, we have been working on creating an indicator of how much a space is a "restorative environment." As a spatial indicator based on Attention Restoration Theory, there was already a method called PRS (Perceived Restorativeness Scale) developed by Terry Hartig and others, which uses subjective questionnaires*8. However, PRS is an indicator of how much outdoor natural environments are "restorative environments" and it is not suitable for indoor spaces. There were also other issues, such as the questionnaire having 26 items, which burdened the participants.

- Tokuhiro

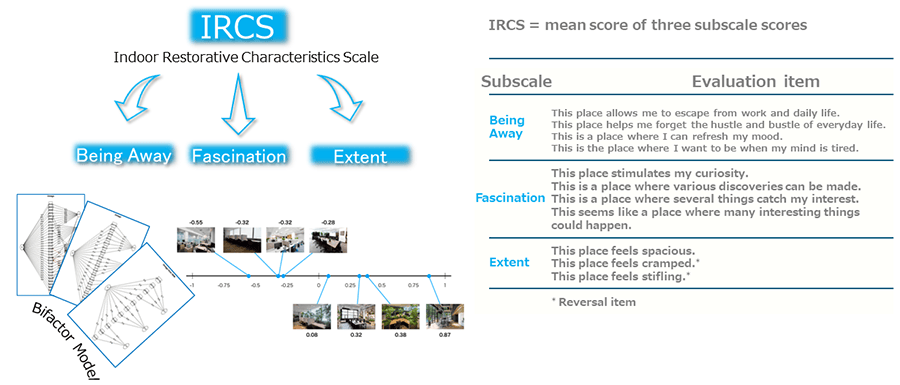

- So, in order to create a new indicator for indoor spaces, we collaborated with Professor Seiji Shibata from Sagami Women's University and created a 30-item questionnaire specifically for indoor use, taking PRS as a reference. Based on the survey results of approximately 1,200 participants, we used a technique called factor analysis using a bifactor model to reduce the questionnaire items to 11. As a result, we found that the three subscales included in PRS (Being Away, Fascination, Extent) were important for evaluating indoor spaces. We named the new indicator the "Indoor Restorative Characteristics Scale (IRCS)" (Figure 3).

-

- Figure 3 Indoor Restorative Characteristics Scale (IRCS)

- What can you learn from this indicator?

- Ikeuchi

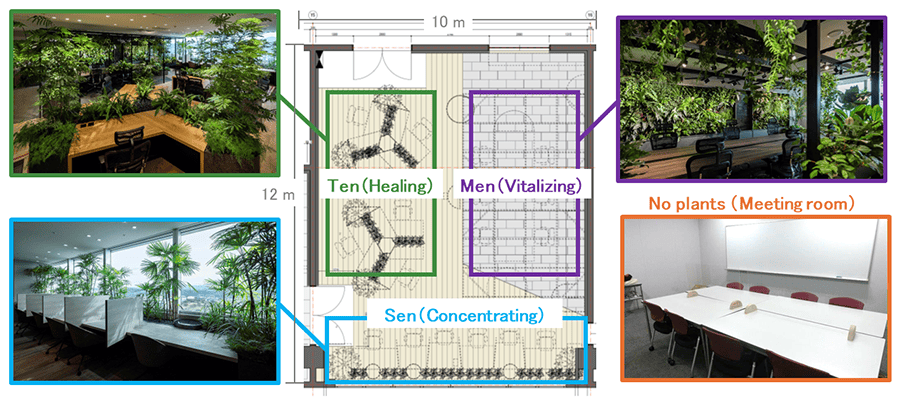

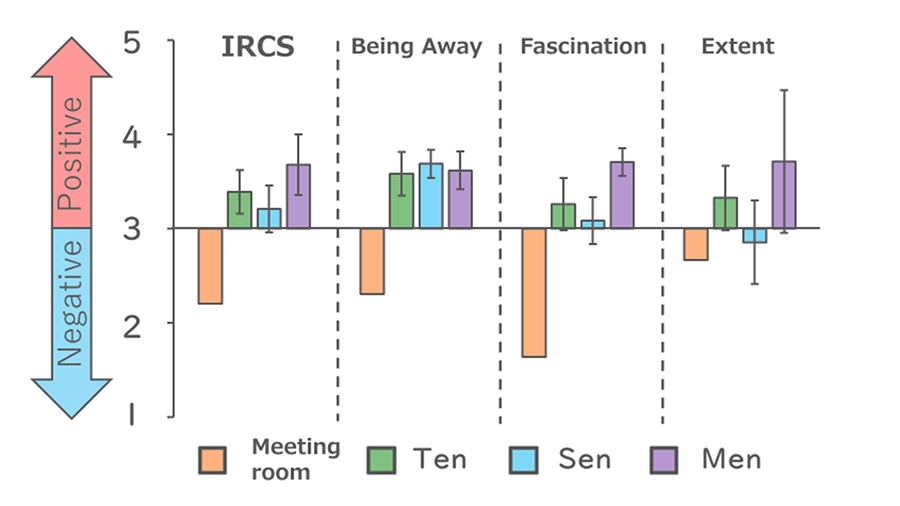

- Using the IRCS, we conducted a spatial evaluation of all the seats in the Genki-office introduced in Part 1 (Three areas: Ten, Sen, Men, with a total of 18 seats. Ten has small leaf-shaped plants, Sen has linear leaf-shaped plants, and Men has large leaf plants) (Figure 4). As a result, we found that the IRCS improved in all seats in the Genki-office compared to those in the typical meeting room, indicating that biophilic design enhances the restorative characteristics of the space. When comparing the Ten, Sen, and Men areas using the subscales of Being Away, Fascination, and Extent, we found that Being Away improved in all areas. This suggests that introducing plants into the space, regardless of the shape of the plant leaves or fixtures, brings the environment closer to being a place where one can "detach from everyday life and refresh" (Figure 5).

-

- Figure 4 The Genki-office (six seats in each area, 18 seats in total)

- Ikeuchi

- In the Men area, which had the highest IRCS, not only Being Away but also Fascination and Extent showed high scores. By planting a wide variety of plants with large and curvilinear leaves, the design can attract interest and create a sense of spaciousness while being surrounded by plants through ceiling greening and wall greening. This design may be the optimal biophilic design for promoting effortless attention.

-

- Figure 5 IRCS of the Genki-office and a typical meeting room

- Can we expect similar restorative effects from artificial plants?

- Tokuhiro

- It is said that artificial plants can also have an effect, but it has been reported that real plants create a more comfortable and relaxed atmosphere*9. Especially in terms of items like "feeling energized," real plants show significantly higher effects. Perhaps humans receive energy by sensing the vitality of plants.

- How can this indicator be utilized?

- Muramatsu

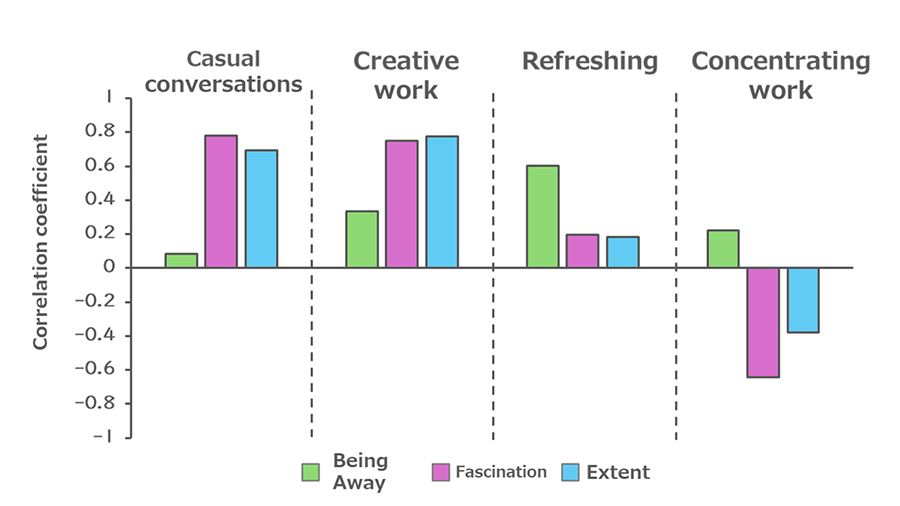

- In addition to creating a restorative environment, it is important to design biophilic features that align with the activities and tasks of the people who will be using the space. Therefore, we conducted surveys specifically related to tasks and behaviors in office spaces, as shown in Figure 6, and examined the correlation between the subscales of IRCS (Being Away, Fascination, Extent). As a result, we found that areas with high Fascination and Extent are conducive to casual conversations and creative work, while areas with high Being Away are suitable for refreshing and cooling down. We also discovered that excessive Fascination and Extent can be distracting and not conducive to concentrating work. By incorporating a balance of the subscales of IRCS as a design guideline, it may be possible to create spaces that are both restorative and tailored to specific kinds of work.

-

- Figure 6 The relationship between the perceived ease of work in the space and its correlation with IRCS

- Please tell us about the future of this research.

- Muramatsu

- In the future, we would like to use techniques such as image analysis to clarify what aspects of spatial design contribute to the psychological effects discussed in this study. It would be great if we could eventually quantify the effects of a space during the design phase and use AI to propose optimal space designs that meet specific functional needs.

Comment from Professor Seiji Shibata at Sagami Women's University, our research collaborator

Various studies have confirmed the psychological restorative effects of nature. However, there is still much we don't fully understand about what types of greening are most effective in enhancing these restorative effects. This series of studies, which focuses on the relationship between leaf shapes and specific psychological functions and seeks to apply it to the design of restorative environments, is a very interesting endeavor. We will continue our research to develop a "recipe" for creating tailored restorative environments for different purposes.

Authors

-

- From left, Akinori Ikeuchi (TCRDL), Masayoshi Muramatsu (Toyota), Kenro Tokuhiro (TCRDL)

References

| *1 | Genki-KûkanTM Research Initiative (Part 1), Reproducing slices of nature in the laboratory, Frontier Research Center, Toyota Motor Corporation. |

|---|---|

| *2 | Genki-KûkanTM Research Initiative (Part 2), Air quality research that opens up a new world, Frontier Research Center, Toyota Motor Corporation. |

| *3 | Genki-KûkanTM Research Initiative (Part 3), Effects of natural air quality on humans, Frontier Research Center, Toyota Motor Corporation. |

| *4 | Genki-KûkanTM Research Initiative (Part 4), Do Genki-KûkanTM spaces really foster health, happiness, and energy?, Frontier Research Center, Toyota Motor Corporation. |

| *5 | Glacken, C.J. 1967. Traces on the Rhodian Shore: Nature and Culture in Western Thought From Ancient Times to the End of the Eighteenth Century. University of California Press. |

| *6 | Ulrich, R.S., R.F. Simons, B.D. Losito, E. Fiorito, M.A. Miles, and M. Zelson. 1991. Stress Recovery During Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology 11, 3:201-230. |

| *7 | Kaplan, R., and S. Kaplan. 1989. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective. New York, Cambridge University Press. |

| *8 | Hartig, T., Kaiser, F. G., & Bowler, P. A. 1997a. Further development of a measure of perceived environmental restorativeness. Working Paper No. 5. Institute for Housing Research, Uppsala Universitet. |

| *9 | Jeong, JE., Park, SA. 2021. Physiological and Psychological Effects of Visual Stimulation with Green Plant Types. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18 (24), 12932. |

Contact Information (about this article)

- Frontier Research Center

- frc_pr@mail.toyota.co.jp